It was a hot afternoon, and the sun struck heavy on a narrow back street in Xi’an. It was a street of ostensible booksellers, specialising in academic materials and study aids. My friend Jing* and I approached the shop she had business with. The sunlight burning through the dusty windows hit almost-empty shelves and the curling covers of neglected textbooks. I waited at a discreet distance, looking at the sun-faded wares that were not the shop’s real merchandise, while Jing talked with the shopkeeper.

Her transaction went more easily than she had feared. She had been worried, because she was returning an expensive purchase to the shop: a set of exam questions and answers for the final English exam at one of Xi’an’s well-regarded universities. Jing had failed the final the previous year and spent that year working tutoring jobs and supposedly studying to re-take the exam. When it came to the crunch, her father worried she might fail again. So, he had sent her a large amount of money to buy the exam paper the week before the exam.

At that time, around 2010, this was apparently very common. Some university teachers, less committed to academic integrity than one might hope, sought to supplement their income by selling exam papers to the middlemen who posed as booksellers. There was a whole street of them, all displaying dusty half-empty shelves while the real wares were hidden away, ready for those in the know.

Perhaps the surprising thing is that after Jing went to the exam-selling street and bought the materials for her exam, she felt conscience-stricken and went back to return it. We were relieved when the shopkeeper agreed to return her money in full. Jing thought her dad would probably be angry, but she’d not tell him until after the exam. (Later, after moving back to her hometown, she took similarly strong unilateral action in breaking off an engagement with a man her parents set her up with, and returning the bride price, while her father was out of town).

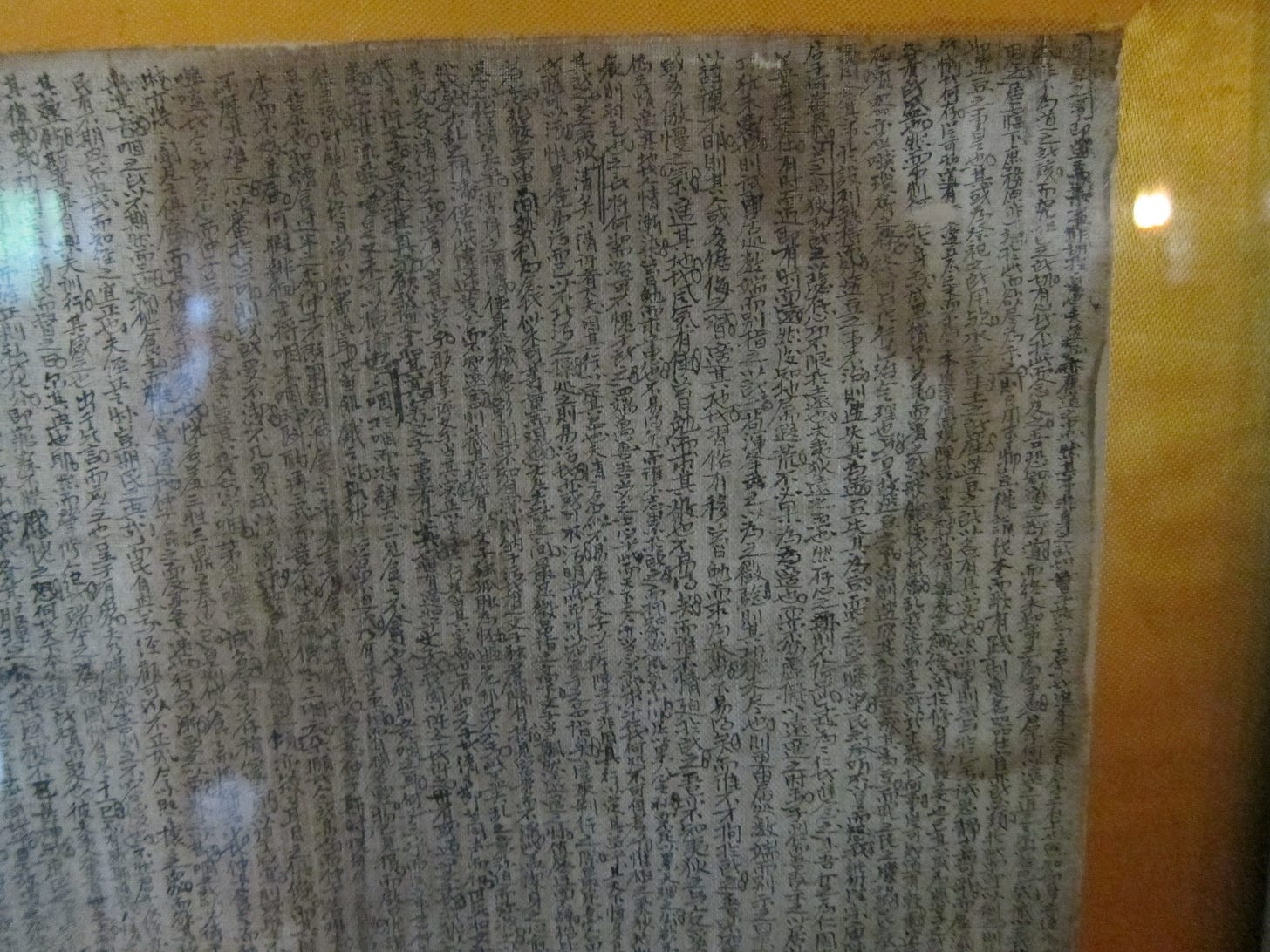

There is nothing new under the sun. I remember visiting the Capital Museum in Beijing a few years back and seeing a selection of artefacts from the ancient Imperial Examination. For nearly a thousand years, the Imperial Examination was used to select candidates for the civil service. Competition was tough. Some men spent almost their whole working lives trying to make the cut, and some never did. There were stringent anti-cheating measures: examinees had to write their essays in tiny individual cells. They also had to sleep and eat in their cell for the duration of the three-day examination. Naturally, some candidates tried to boost their chances of success with bribery or smuggled crib sheets hidden in their underwear or the sleeves of their robes. The display in the Capital Museum showed some examples.

There is nothing new under the sun. Our students are not hiding cheat sheets in their underwear, but they are definitely trying to game the system with their homework tests this semester.

There will always be students everywhere trying to game the system, so it shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s just a bit more annoying this semester, because we were trying to move to more continuous assessment that would allow students to monitor their own progress a bit better than a big-bang final. In previous years, we had a traditional closed-book exam at the end of the semester to assess students’ listening and reading skills. This year, we replaced this with weekly listening and reading tests, done online. After a couple of weeks, we noticed that most students had suspiciously high scores and were finishing the tests in suspiciously short times. We tweaked some of the settings on the software system. No effect. We tweaked some more. Still no effect. At the end of class one day, when there were just a couple of my more reliable students left in the room, I asked them whether they knew of people passing round the answers.

“No,” said one of them cautiously. “But I think that some students do the test together. They look at it on one computer then everyone else does it very fast.”

There’s nothing we can do about it at this point, given that we can’t force them into Imperial Examination cells every week for the homework tests. Perhaps next year it’ll be a return to the good ol’ final exam with paper and pen.

This is only a minor headache compared to the minefield of AI. In our writing classes, I now find myself scanning every assignment for signs of ChatGPT and its cousins. In the presentation classes, I listen to students spout purple prose like “we must navigate the turbulent waters of electric vehicle research with aplomb.”

“Did you write that or did ChatGPT write it?” I ask the offending student.

“Not ChatGPT,” he says, his face turning slightly red.

“Did you write it? What does it mean? What does aplomb mean?”

“I didn’t use ChatGPT, but my friend gave me a draft of his thesis presentation and I used that to help me.”

“Did he use ChatGPT?”

“I don’t know.”

I told him to scrap it and rewrite his presentation using his own words.

For now, AI-generated text stands out fairly obviously when our students use it. That’s probably not going to last. (I read an interesting paper recently about how in a study at Durham University, markers of short physics essays were unable to reliably distinguish between human and AI authorship1). Students are also using AI to cheat in other classes. One bioinformatics lecturer told us over lunch how one student even managed to hack a way to use ChatGPT to write code for him in a programming exam, in a closed exam room with computers locked to a single website. At that point, the effort that’s gone into cheating seems more than the effort needed to actually master the material!

We definitely need to teach students how to use AI properly and ethically. And we need to get the message through to them that taking shortcuts, whether AI or crib-sheet underwear, is harming themselves and not us; that learning to understand what the material really means and how to use it is more important in the long run than getting 100% on any particular test.

This week we have midterm presentations for our first-year students. They have to present a research paper that they have read. It’s a tough assignment, I fully expect that some of them will recite memorised scripts in flowery prose generated by their favourite AI. I fully expect that those students will struggle when I ask them questions in the Q&A, and I sincerely hope that their grade will shock them away from such shortcuts in future. I also expect that there will be many students who have worked diligently and done their best, and I hope their grades will reward and encourage them.

I guess that sometime in the future, AI in education will be used effectively and ethically and not just as a fancy way for students to cheat. But I’d bet my bottom dollar that there will then be some new (or old) way to cheat, and that some students will put all their effort into the shortcuts while others toil with the true work. There’s nothing new under the sun.

New to Canal Town? Start here for an introduction!

Miss my last post? Catch up below!

Tombsweeping and the empty tomb

It’s Eastertime. Spring flowers are out in force, and the weather has turned warm, but not yet too warm. Perfect for an Easter Sunday picnic in the park after church — a low-key way to enjoy friendship and food, even for those who don’t especially mark the holiday. I’m making miniature pork pies (that quintessential British picn…

Will Yeadon, Elise Agra, Oto-obong Inyang, Paul Mackay and Arin Mizouri. (2024) “Evaluating AI and Human Authorship Quality in Academic Writing through Physics Essays”, arXiv:2403.05458

Cheating is such a strange issue to me. I understand where the desire comes from - we were all students with the pressure of passing and doing well on us at one point or another after all - but it comes from such a short sighted place. Before I was an RA, I taught anatomy and physiology for pre-nursing students. My second semester teaching A&PII we had a problem where for their weekly quizzes, students for earlier sections were giving answers to students in later sections.

What they didn't realize was that the prenursing program at my university is very competitive and it made it so students later in the week were getting near perfect scores making students earlier in the week look like they were falling behind. It was extremely clear and fortunately rectified easily, but it was a mess. I remember a student approaching me after the class where we announced (all the TA's and professors) that we knew what was going on. She was crying because she felt like she was doing well but refusing to cheat was making her lag behind in the class rankings. It was an absolute mess that's for sure.

It was a strange to have to inform people that cheating wasn't helping them get ahead, it was just making their cohorts fall behind in the rankings.